Enslaved to Soldier

67 Black men from Liberty enlisted in the Union army. 26 of these men died during the war and another 4 are believed to buried in Fairview Cemetery, without a headstone. Using the records of the United States Colored Troops, we share their stories and honor their service.

Unknown soldier at Benton Barracks, Missouri

While researching the names for the Legacy Memorial, we came across the Union enlistment records of David Drake (Blue), who is believed to be buried in Fairview Cemetery. This discovery brought up many questions about Black men serving in the Civil War: How many men from Liberty enlisted? How did enslaved men come to be enlisted in the army of the Union? What happened to them after the war? Are any of them buried in unmarked graves like David Drake?

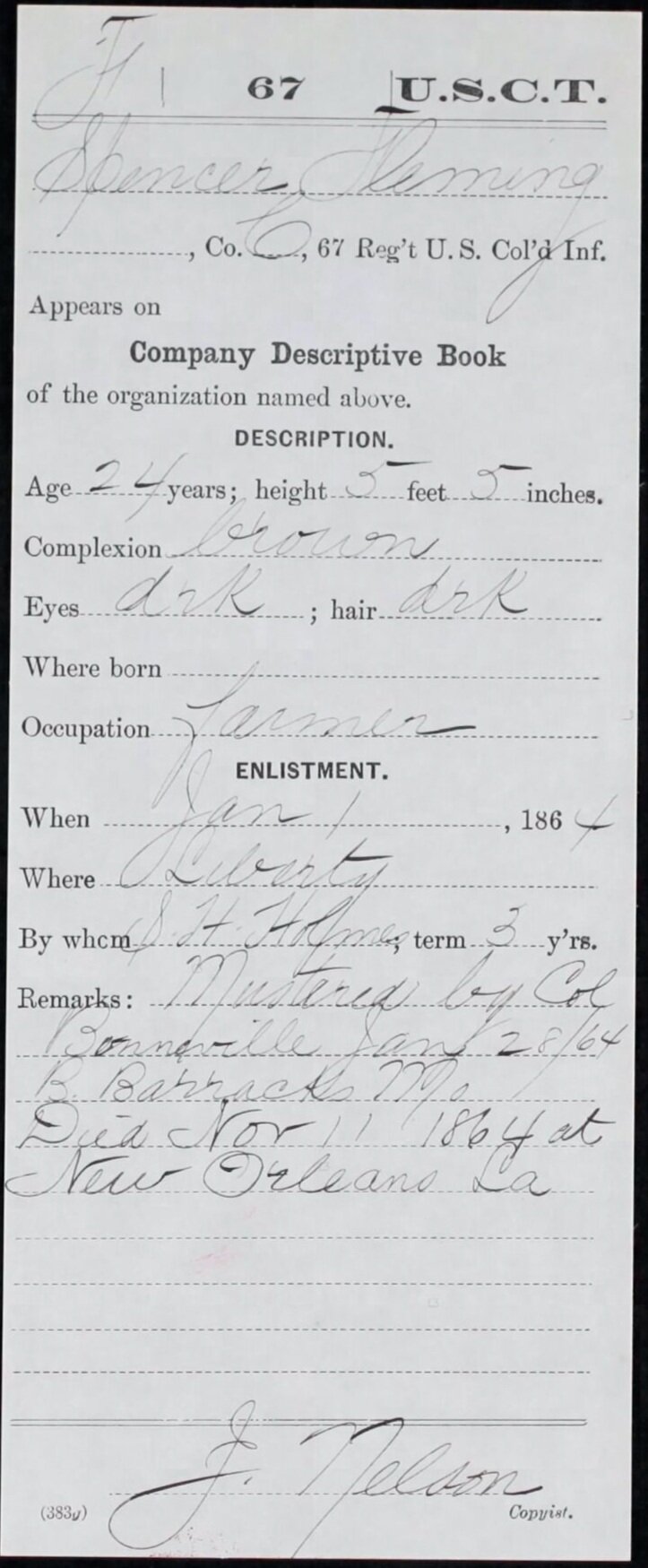

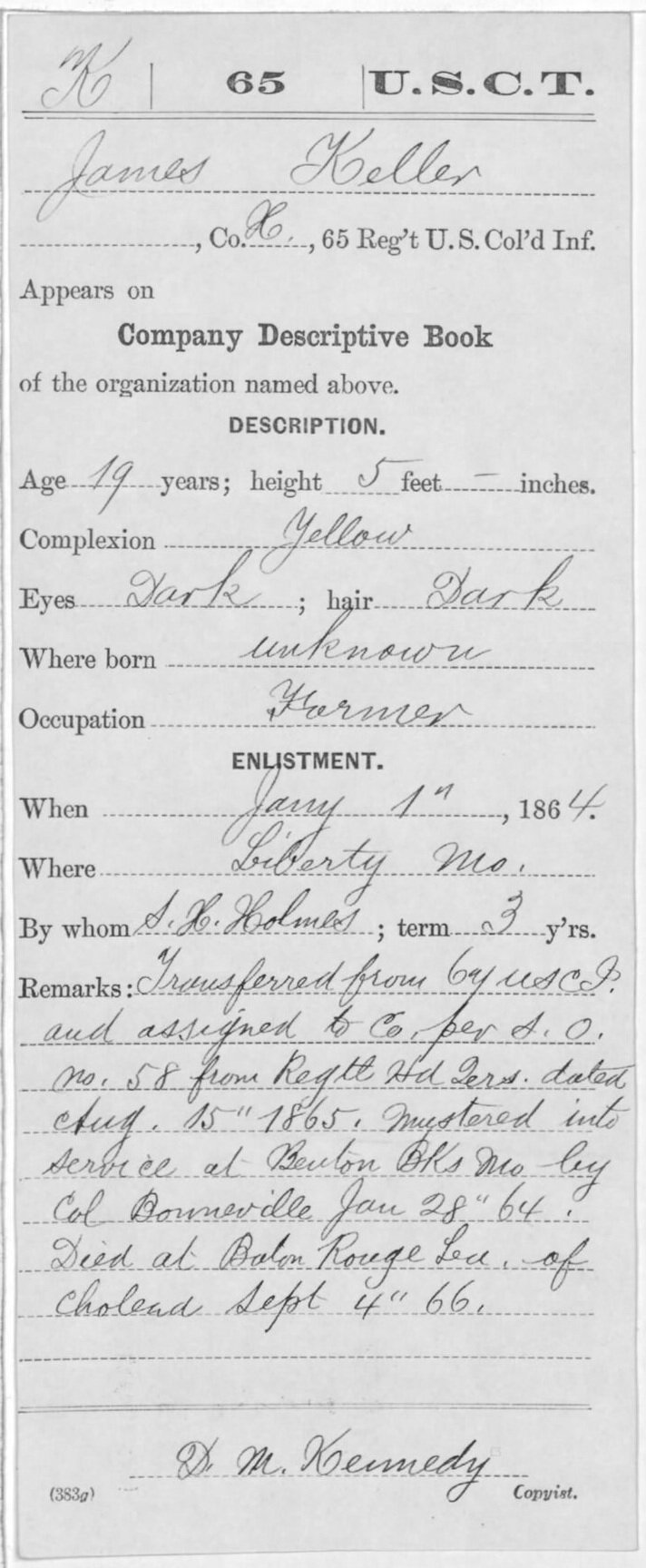

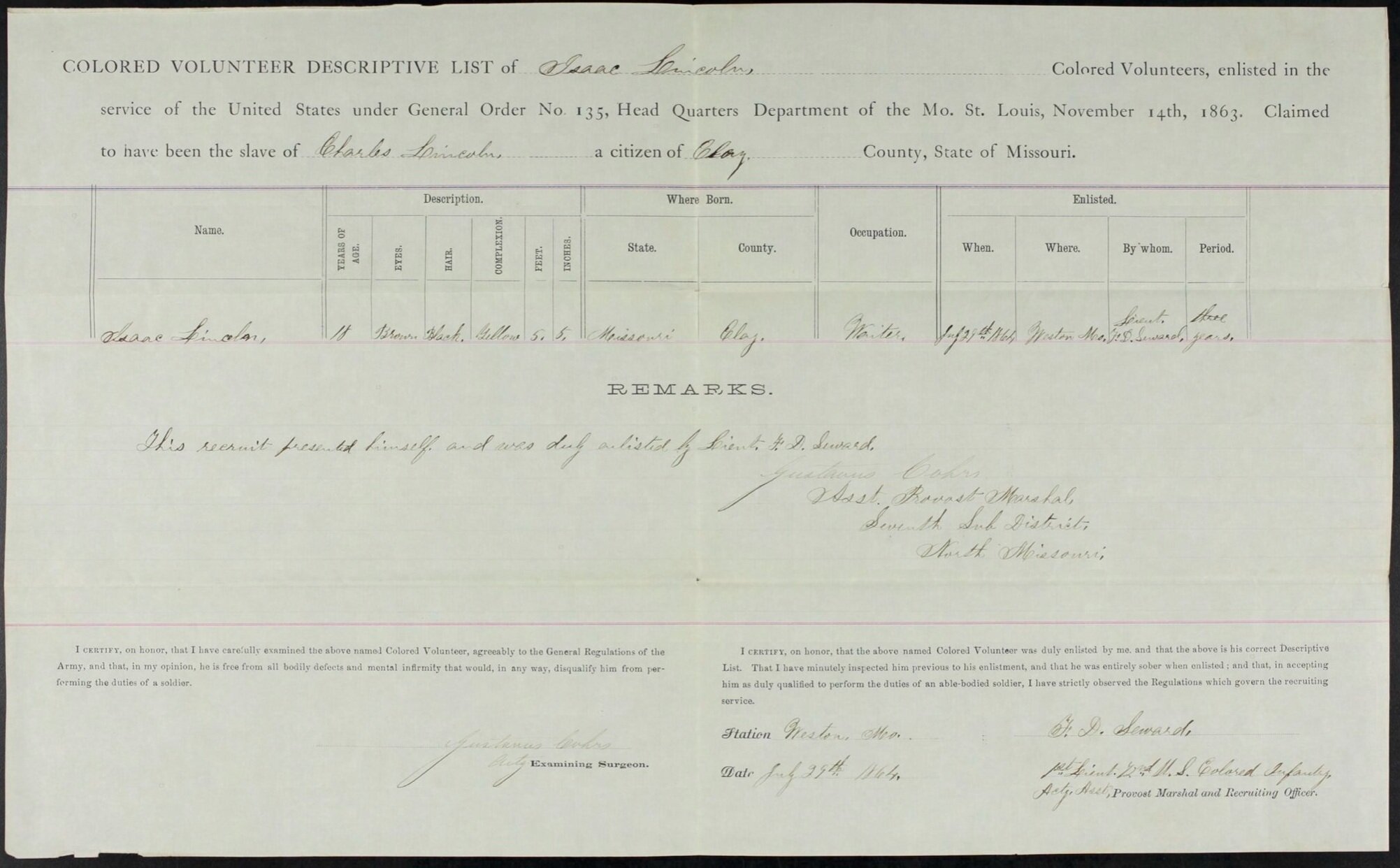

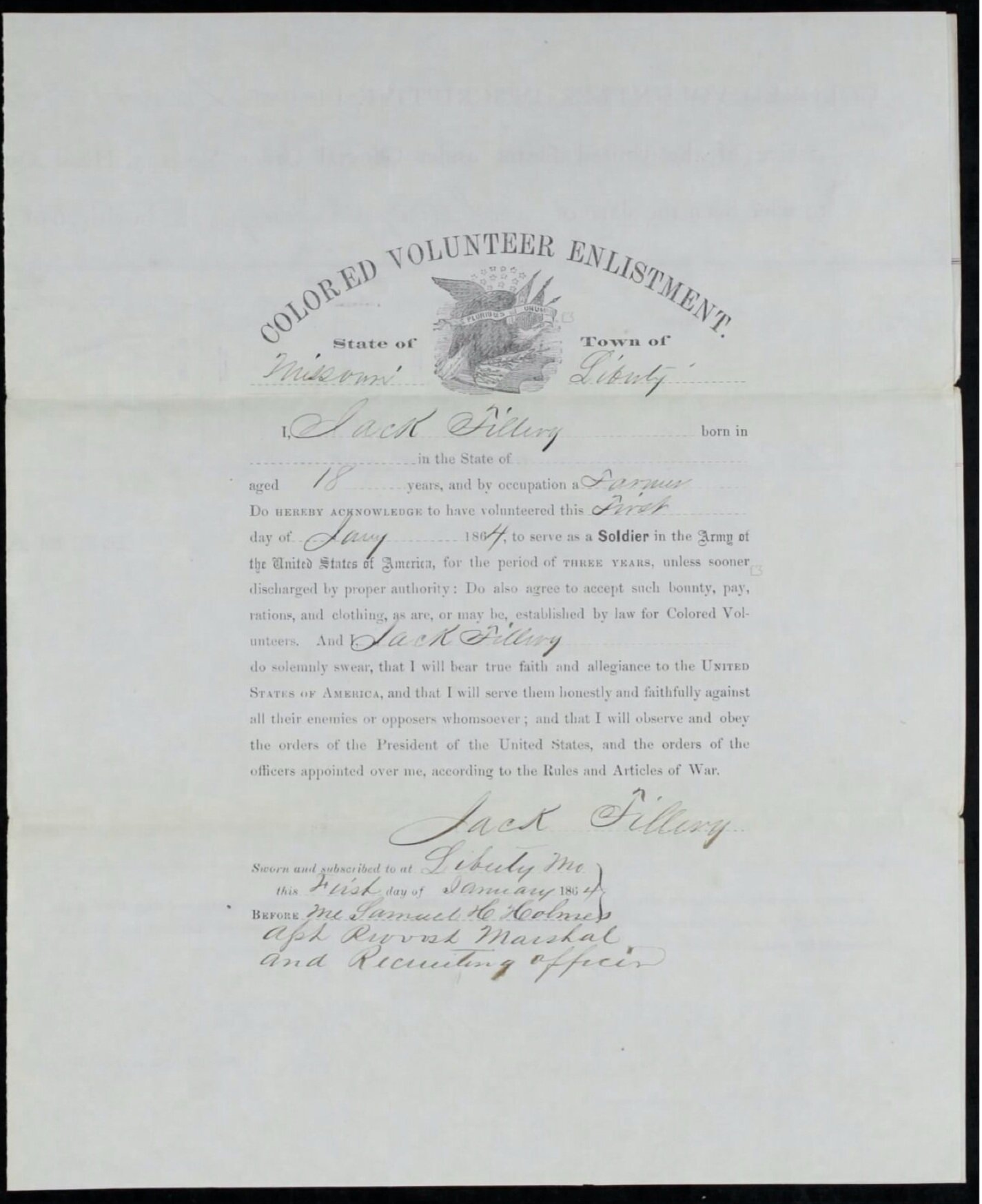

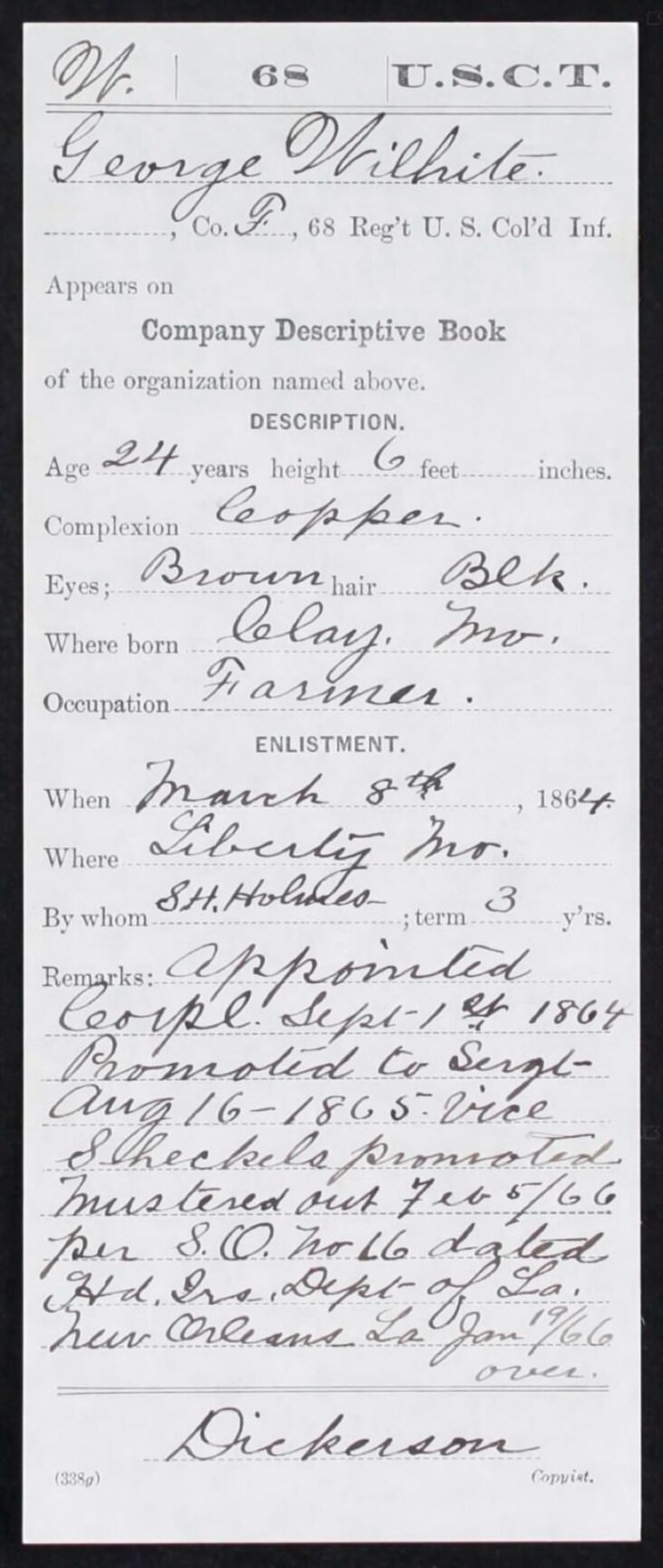

These questions led to the unexpected project of researching Civil War records in the hope of finding the names of all the Black men from Liberty who served. Thanks to the preservation of military records by the National Archives (hosted on Fold3) and the St. Louis County Library Genealogy Department, we were able to track down the descriptive records for 67 Black men who enlisted at the Liberty Recruitment Station of the Union Army. What makes these records especially powerful is that they include a physical description of the man enlisting — his height, skin color, hair color, and eye color. There is also a field that notes the recruit’s occupation, with most of them listed as “farmer” or “laborer”. These men were enslaved, farming the land owned by someone else or laboring in the house of their enslaver. However, this did not change their answer or how they saw themselves. When asked their occupation, they declared they were a farmer, a mechanic, or a laborer, not a slave. We have collected hundreds of records, and this page contains a sample of them, one document for each of the 67 men.

Liberty Tribune announcing the enlistment of Black men into the Union army

The debate on whether or not Black men should be allowed to enlist in the army was contentious, especially in states like Missouri, which remained a part of the Union while firmly protecting the institution of slavery. While we have records of these 67 men, we unfortunately do not have official record of every man who served. Some men from Liberty may have gone to recruitment stations in other cities or their records may have been lost. Additionally, those who served in roles such as teamsters, cooks, musicians, and blacksmiths were often not officially enlisted with a regiment and therefore do not have military records. This was usually the case for men who were physically unable to join the ranks or boys who were too young to enlist and instead assisted with the horses and making camp. William Slaughter, who served as a teamster and does not have official military records, is buried in Fairview Cemetery. We honor the men and boys who served in any capacity because even though records of their service may not exist, it does not downplay their bravery or sacrifice.

The men from Liberty and the surrounding area were enslaved prior to their enlistment, and found themselves at the recruiting station for different reasons:

They received permission from their enslaver to volunteer for service.

They were a Freedom Seeker and sought out the Union army for protection from capture. This is usually noted in their enlistment record as “recruit presented himself”.

They were forced to enlist by their enslaver. Enslavers received a $300 compensation if they pledged loyalty to the Union and enlisted the man/men they enslaved. With the growing possibility of emancipation in the state, some enslavers saw this as a last chance to get their money’s worth.

They were taking the place of their enslaver’s draft card.

Upon medical examination, some of the men were discharged for physical disability or illness. Others were turned away because it was discovered the didn’t meet the minimum age requirement. What happened to them after they were dismissed is unknown, but it is most likely they were returned to their enslaver.

Those who were deemed physically fit for service joined the ranks of the 18th, 65th, 67th, and 68th regiments of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Most were mustered in at the Benton Barracks in St. Louis and then sent to cities throughout the South, including Port Hudson, Morganza, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, Nashville, and Memphis. The men were paid $10 a month ($3 less than white recruits) and were required to withhold $3 a month to cover the cost of their supplies. Through military and census records, we were able to trace what happened to some of them during and after the war:

26 are recorded as dying during their term of service, in battle or of disease

4 are believed to be buried in Fairview Cemetery, without a headstone or veteran’s honor (5 including William Slaughter)

4 are believed to have returned to the area, but are buried elsewhere

2 are recorded as absent from their post shortly after enlistment, seeking freedom in Kansas.

What happened to the rest of the men may forever be unknown. It is possible their death was unrecorded or they were captured by the Confederate army. It’s possible they finished out their term of service and decided to change their name to one of their own choosing and live wherever they wanted. Or perhaps they began the desperate journey of seeking out family members and loved ones separated by the institution of slavery.

Whatever the end to their story, we honor each of these veterans here. Liberty was once their home and this is the land where they would have been laid to rest if war hadn’t taken them. It is with great respect that we acknowledge the bravery of these men, and honor all the African Americans who served.

Wallace Arthur - term of service ended, buried in Leavenworth, KS

Green Baker - died May 31, 1864, Benton Barracks

Henry Berry - died August 1, 1864, Port Hudson

Joseph Beasley - believed to have fled to Kansas

Henry Bird - term of service ended, buried in Lansing, KS

Robbin Calhoun - enlisted at the age of 16 and believed to have fled to Kansas

James Turnham - term of service ended, post war location unknown

Henson Beasley - dismissed due to age and disability

Allen Claybrook - term of service ended and returned to Liberty. Strong possibility he is buried in Fairview, awaiting documentation.

Samuel Denny - died November 19, 1864, Morganza

Sam Donaldson - post war location unknown. "This recruit presented himself at my office" noted on enlistment record

Nelson Doniphan - promoted to sergeant and corporal, term of service ended, post war location unknown

David Drake - term of service ended and returned to Liberty. Strong possibility he is buried in Fairview, awaiting documentation. Chosen name: David Blue

Zack Estes - unknown

Harry Estes Slaughter - term of service ended, buried in Fairview. The name on his records fluctuate between Harry and Henry (sometimes on the same page). Estes was his last name upon enlistment; Slaughter was his last name after emancipation.

Milton Thomason - promoted to corporal, died May 16, 1865, Mobile

Horace Ringo - died April 9, 1864, Port Hudson

Martin Robinson - died September 6, 1866, Baton Rouge

Benjamin Robinson - appointed to corporal, died April 16, 1865, Nashville

John Walker - died February 8, 1864

George M Walker - died August 1, 1864

Dennis Everett - dismissed by mustering officer

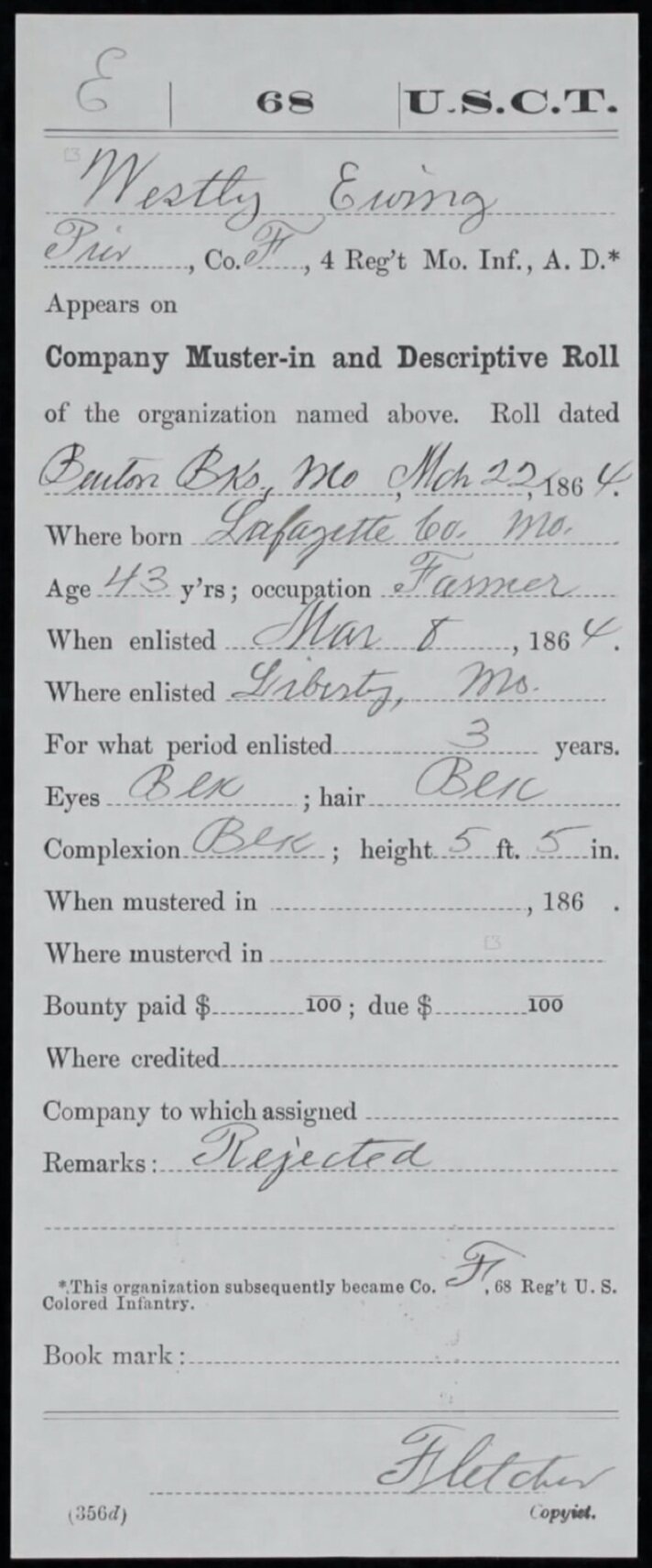

Westley Erring (written as Ewing) - dismissed upon medical examination

David Mosby - dismissed upon medical examination

Doniphan Pryor - discharged after illness, post war location unknown

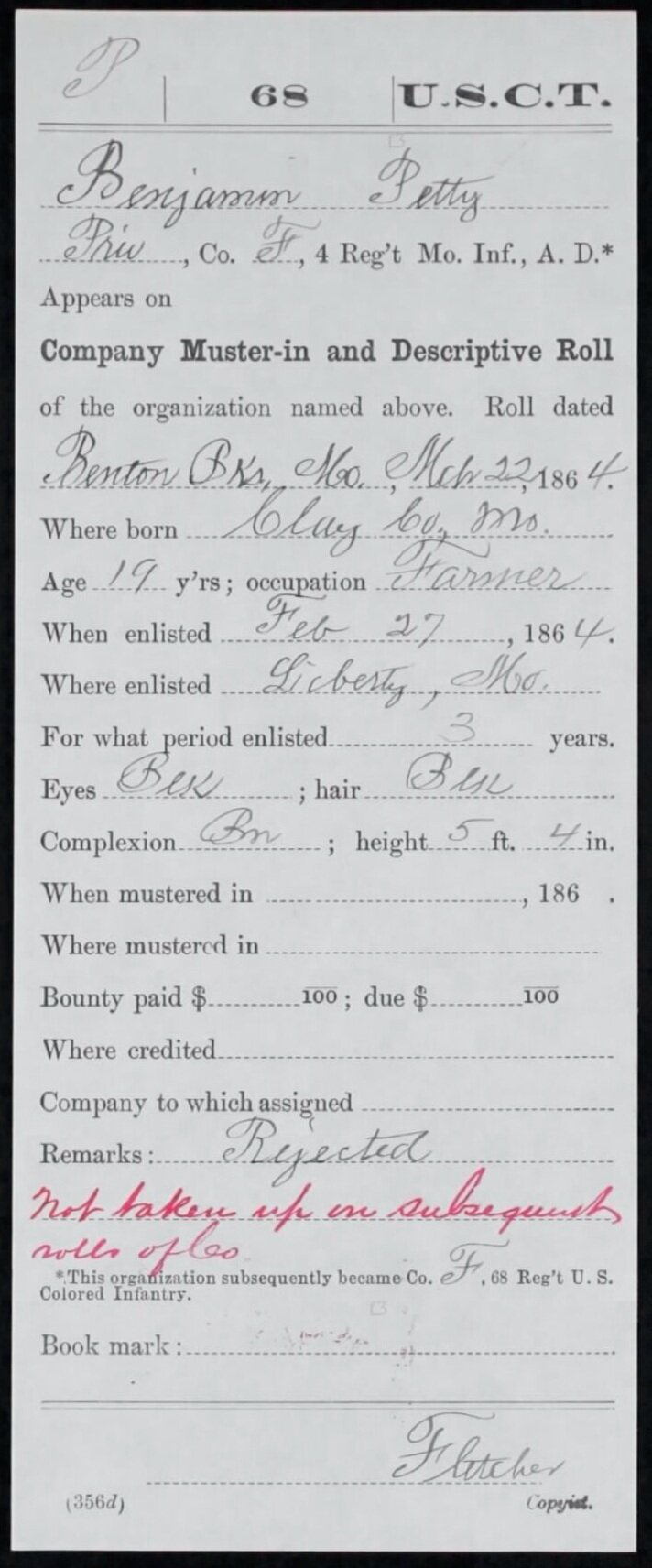

Benjamin Petty - dismissed upon medical examination

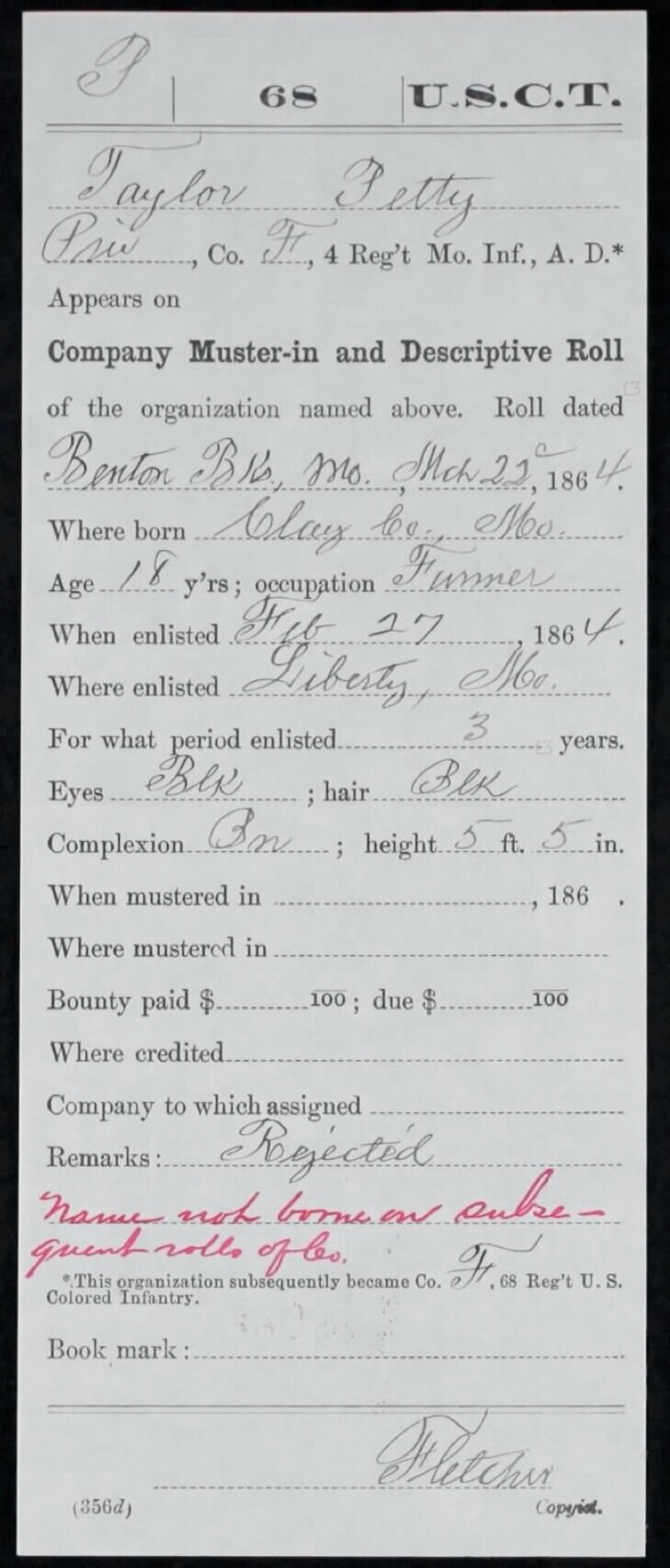

Taylor Petty - dismissed "because of being only 16 years old"

Thomas J Petty - term of service ended, post war location unknown

Rufus Ringo - died October 13, 1864, Morganza

James Talbott - died September 1, 1864, Morganza

Samuel Thorp - died February 13, 1864

Benjamin Thompson - term of service ended, post war location unknown

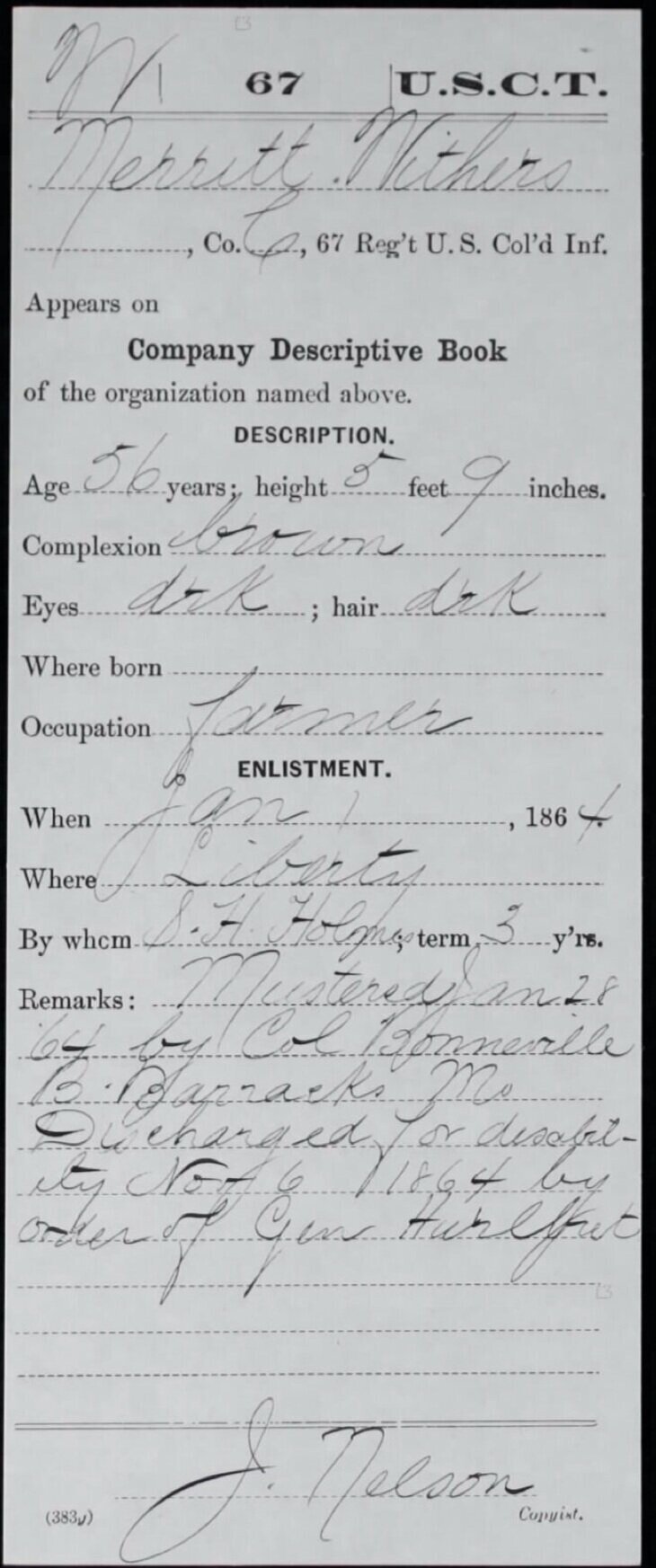

Merritt Withers - term of service ended and returned to Liberty. Possibly buried in Fairview or with his family in the enslaved section of the cemetery on Withers Plantation

Frank Thorp - on duty as musician and cook, discharged for disability, term of service ended, post war location unknown

Charles Thompson - promoted to sergeant, term of service ended, post war location unknown

Jerry Field - dismissed by mustering officer

Spencer Fleming - died November 11, 1864, New Orelans

Samuel Flemming - died October 8, 1864, Memphis

Mason Fowler - died April 16, 1864, Port Hudson

George W Grooms - term of service ended, post war location unknown

Isum George - died April 10, 1864, Benton Barracks

Franklin Fritzland - promoted to sergeant, died April 8, 1865, New Orleans

Jack Gant - term of service ended, believed to be buried in Kansas

John Hadley - term of service ended, post war location unknown

Thomas Hall - unknown

Joseph Howard - term of service ended, post war location unknown

Parker Hampton - died April 21, 1864

James Keller - died September 4, 1866, Baton Rouge

Elijah Laffoon - unknown

Thomas Land - died February 14, 1864

Isaac Lincoln - unknown. "This recruit presented himself at my office" noted on enlistment record

Jack Lincoln - dismissed upon medical examination

Charles McCorkle - died July 30, 1864

George Minter - unknown. "This recruit was presented by his master" noted on record

Henry Minter - dismissed upon medical examination

Benjamin Peters - left sick November 9, 1864, expected to have died

Madison Mosely - unknown

George W Rogue (written as Pogue)- died May 15, 1864, New Orleans

Marcellus Pence - records seem to indicate he was brought before the Court Martial in New Orleans for failing to pay for supplies, post war location unknown

Woodford Pickett - term of service ended and returned to Liberty. Possibly buried in Fairview or with his family in the enslaved section of the Pickett private cemetery

Mat Robertson - died October 10, 1864, Morganza

Jack Tilley (Tillery) - unknown

Randall Talbott - term of service ended, post war location unknown

Jerry Rice - term of service ended, post war location unknown

George Walker - died November 6, 1864

Joseph Welton - died July 20, 1864

George Wilhite - promoted to sergeant, term of service ended, post war location unknown

Sources:

“Civil War Service Records (CMSR) - Union - Colored Troops 56th-138th Infantry”. Fold3. April 5, 2014.

“Descriptive Recruitment Lists of Volunteers for the United States Colored Troops for the State of Missouri, 1863-1865”. St. Louis County Library.

Keller, Rudi. “67th USCT Infantry Roster”. Columbia Tribune. March 11, 2014.

Mutti Burke, Diane. "Slavery on the Western Border: Missouri’s Slave System and its Collapse during the Civil War". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library.

Weidman, Budge. “Black Soldiers in the Civil War: Preserving the Legacy of the United States Colored Troops”. The National Archives. March 19, 2019.

Make a donation.

Your contribution matters and is appreciated. Every dollar gets us closer to building the memorial and honoring the African Americans buried on this hallowed ground.